Marginal Revolution

The most successful economics blog in the world is called Marginal Revolution.

That is not an accident.

It could have been called Markets and Power, or Inequality Today, or Political Economy. It could even have been called Capitalism Explained. Instead, it is named after a nineteenth-century intellectual earthquake: the marginal revolution. A quiet reminder that modern economics begins not with slogans or moral postures, but with a way of thinking.

That reminder matters today more than we like to admit.

The marginal revolution

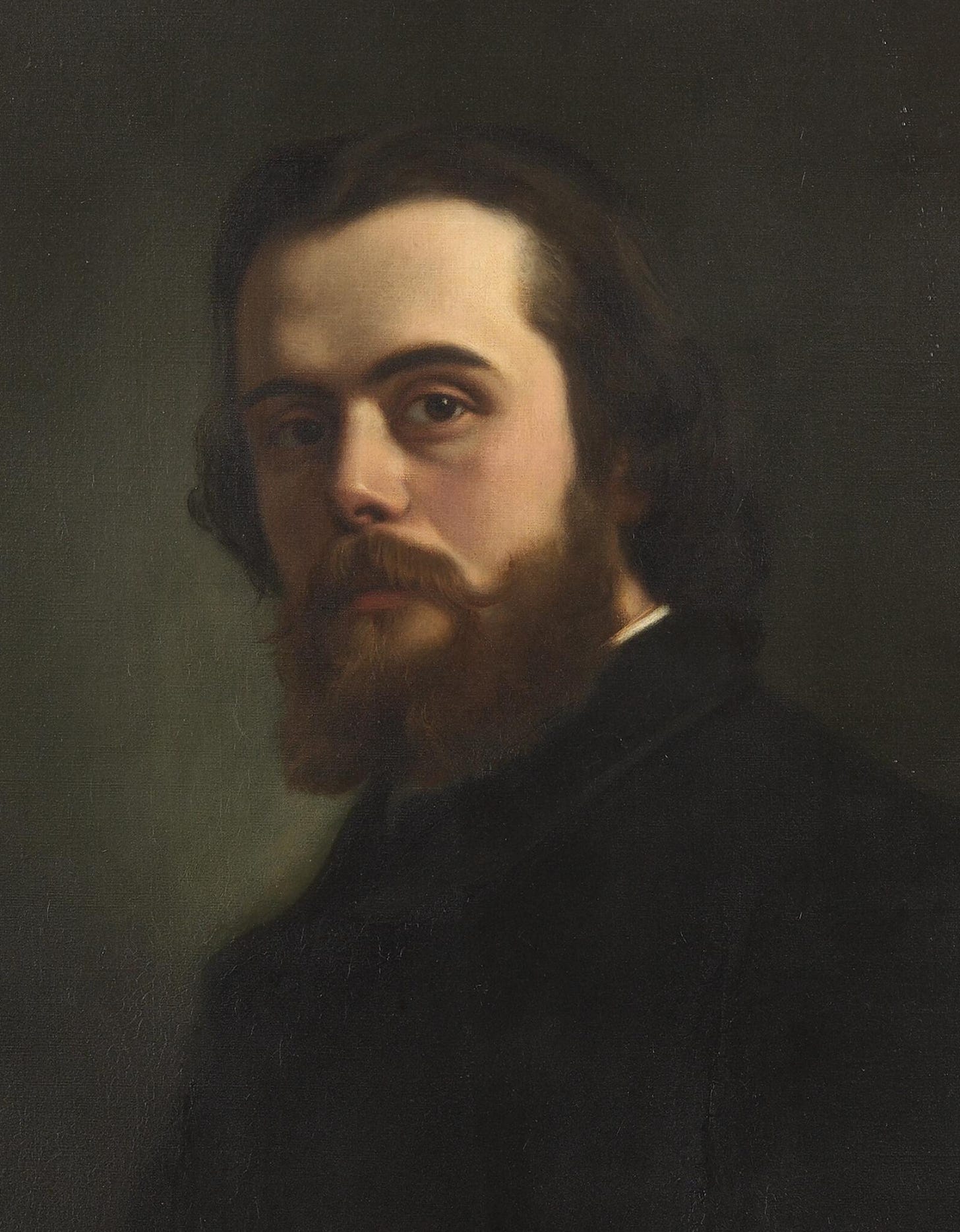

In the 1870s, almost simultaneously and largely independently, three economists overturned classical political economy. William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras broke with the Ricardian tradition that explained value through labor, costs, or embedded substance. Value, they argued, does not come from the total amount of work put into something. It comes from the last unit—from what economists would soon call marginal valuation.

This was not a semantic tweak. It was a change in how economic reasoning itself works. Decisions are not made by comparing wholes; they are made at the margin. Not “is water useful?” but “how useful is one more glass of water, given how much I already have?” Not “is labor important?” but “is the next worker worth hiring at this wage, given current output and technology?”

A generation later, Alfred Marshall did what the greatest synthesizers do: he turned a revolution into a toolkit. Supply and demand curves, elasticities, consumer surplus, marginal cost and marginal product—Marshall gave economists a language that could actually be used. From that point on, modern economics was possible.

The core insight was simple, but devastatingly powerful:

Economic choices are made at the margin, not in the aggregate.

Why this changed everything

Once you take the marginal perspective seriously, the world looks different.

Firms hire workers up to the point where the value of the marginal product equals the wage. Consumers trade off goods until their willingness to substitute at the margin aligns with the market’s trade-off—relative prices. Investment flows to activities where the expected marginal return is highest. Growth happens because resources—labor, capital, ideas—move from low-value uses to higher-value ones.

Without marginal analysis, you cannot explain prices. You cannot explain allocation. You cannot explain why reallocation—sometimes painful, often disruptive—is the engine of productivity growth. You cannot explain why protecting existing structures, however well-intentioned, so often leads to stagnation.

The marginal revolution is why economics stopped being an exercise in moral arithmetic and became a discipline focused on mechanisms.

When marginal analysis disappears

What is striking is how often public debate slips back into pre-marginal reasoning—especially when moral intuitions are strong.

We see microeconomics arguments based on levels instead of changes, on identities instead of incentives, on stocks instead of flows. We see decisions justified by who someone is rather than by what happens at the margin. We see calls to preserve structures because they exist, to freeze allocations because change feels uncomfortable, to judge outcomes by averages rather than by trade-offs.

From a marginalist perspective, these arguments are not just wrong; they are incoherent.

Consider a few common mistakes that reappear whenever marginal thinking is abandoned:

Treating the owner’s biography—wealth, identity, status—as if it entered the firm’s marginal conditions. It does not.

Confusing redistribution with allocation. Redistribution is a legitimate political choice, but it should not be smuggled into production decisions where it distorts incentives and blocks reallocation.

Ignoring opportunity cost. Resources used to sustain one activity are resources not used elsewhere. The relevant question is always: what is the next best alternative?

Believing that efficiency is static. In reality, efficiency is dynamic, and depends precisely on the ability of resources to move when margins change.

Reallocation is not a bug

One of the most uncomfortable implications of marginal analysis is that reallocation is essential. Labor and capital must sometimes leave declining uses so they can enter expanding ones. That process is rarely smooth, and never painless. But blocking it does not make an economy more humane; it makes it poorer.

The twentieth century gave this insight a name. Joseph Schumpeter called it creative destruction. János Kornai warned that when losses are systematically covered—when budget constraints are soft—adjustment never happens, inefficiency becomes chronic, and stagnation follows.

Marginal analysis explains why. If losses have no consequences, margins lose meaning. Prices stop signaling scarcity. Productivity differences stop guiding allocation. The economy becomes a museum of preserved structures rather than a system that adapts.

Why this still matters

It is tempting, especially in polarized times, to replace mechanism with morality. To judge economic decisions by intentions rather than by incentives. To treat outcomes as expressions of virtue or vice.

But that temptation is precisely what the marginal revolution was meant to overcome.

Marginalism does not deny morality. It simply insists that morality cannot substitute for analysis. If we care about employment, innovation, growth, or even redistribution itself, we need to understand how choices respond at the margin. Otherwise, well-intentioned interventions end up doing the opposite of what they promise.

This is why the name Marginal Revolution still resonates. It is not nostalgia. It is a warning.

A quiet conclusion

In many discussions, the distinction between allocation and redistribution, between constraints and intentions, quietly disappears once marginal analysis is set aside.

The marginal revolution was not a technical curiosity. It was the moment economics learned how to think.

Let’s not forget that.

***If this essay resonated with you, you can subscribe to my Substack for regular reflections on economics, politics, geopolitics, AI, and literature.

*** Disclaimer: I used ChatGPT-5.2. as an editorial and language-refinement tool. The ideas and arguments are entirely my own, and I take full responsibility for them.

If you want to see where marginalism has been lost, come to France.

Excelellent thank you Sebastian!