When “Preferences Changed” Stops Being an Explanation

I have become increasingly uncomfortable with a move that has grown common in contemporary economic discourse. A behavior changes, a social pattern shifts, a political equilibrium dissolves — and the explanation arrives quickly and effortlessly: preferences have changed. People value different things now. Norms evolved. Tastes shifted. Case closed.

Sometimes, of course, that may be true. But as a general explanatory strategy, it is deeply unsatisfying. Too often it feels ad hoc, almost tautological. Behavior is different because preferences are different; we know preferences are different because behavior is different. The explanation absorbs the phenomenon instead of illuminating it. It ends inquiry rather than opening it.

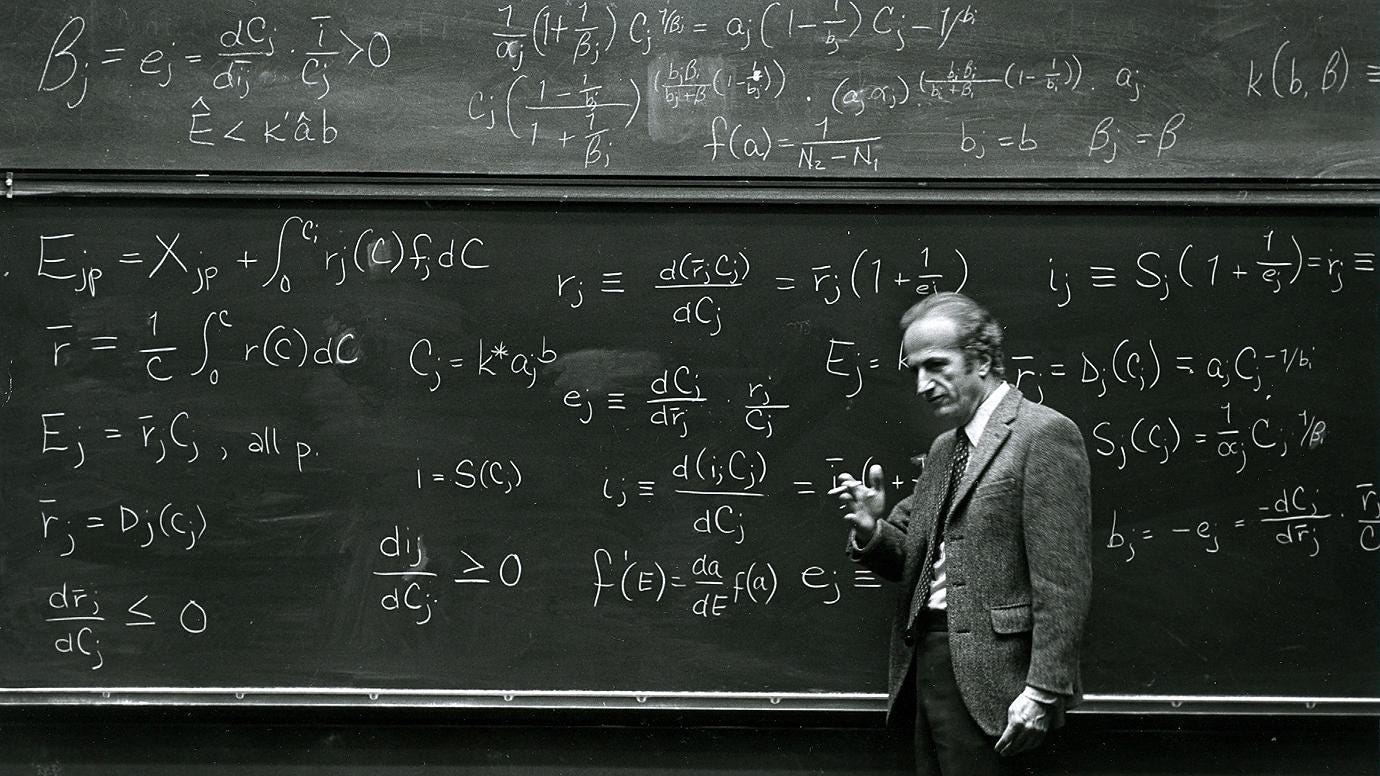

This discomfort is not new for me. In a recent essay on Gary Becker, I argued that the lasting power of his work lay less in any single application than in a methodological discipline: do not move preferences lightly, and never without a mechanism. Becker’s ambition was to build a general science of human behavior without turning tastes into a residual that explains everything and nothing.

Becker’s strategy is often misunderstood. He did not claim that human motivations are frozen or immune to history. His point was methodological rather than psychological. Preferences were to be treated as stable not because people never change, but because explanation requires discipline. If tastes shift whenever the data demand it, theory becomes unfalsifiable. So Becker pushed economists to load the explanatory burden onto constraints: prices, income, time, technology, institutions, information. Those can change — sometimes quickly — and when they do, behavior changes with them.

This is why Becker’s work constantly expanded the notion of constraints. Time entered the utility function. Human capital accumulated. Habits formed. Social interactions mattered. What looked like a change in motivation was often the cumulative result of past choices made under constraints. Stability at the level of basic motives was perfectly compatible with persistence, path dependence, and slow-moving change in behavior. Change was real — but it had to be earned.

From this perspective, the modern habit of invoking preference shifts as a first-order explanation is a retreat, not an advance. It short-circuits analysis. It replaces mechanisms with labels. A preference change that is not itself explained is not a theory; it is a name for our ignorance.

At this point, a fair question arises — one I have asked myself. Haven’t I recently relied on models in which preferences do evolve over time? Haven’t I used the Alberto Bisin–Thierry Verdier framework, in which aggregate behavior shifts as traits are transmitted across generations? Isn’t that precisely the kind of explanation I am criticizing here?

The answer is no — and the reason is that these models are disciplined in exactly the Beckerian sense.

In the Bisin–Verdier framework, preferences do not drift freely from one time to the next. What changes is the composition of a population over time. Traits are transmitted imperfectly across generations. Parents and communities invest in socialization, at a cost. Matching is assortative. Institutions reinforce some traits and penalize others. The result is slow, cohort-based change.

What looks like a “preference shift” at the aggregate level is, at the micro level, the outcome of many constrained optimization problems interacting over time. Preferences are not free parameters; they are state-dependent outcomes of social and economic processes. The models make strong predictions: persistence, path dependence, resistance to rapid reversals. They tell us not only what should happen, but what should not happen.

This is the crucial distinction that often gets lost. The issue is not whether preferences can change. It is whether their change is explained.

“Preferences changed” becomes an explanation only when it generates counterfactuals that would otherwise not arise.

Becker understood this instinctively. His refusal to invoke tastes casually was not dogmatism; it was respect for explanation. And when modern models of cultural transmission take preferences seriously as an object of analysis, they do so — or should do so — in that same spirit.

If we forget this discipline, preferences become a universal solvent. If we respect it, preference formation becomes one of the hardest and most interesting problems economics can study.

References:

Gary Becker (1993). The Economic Way of Looking at Behavior.

Nobel Prize Lecture, December 9, 1992. Reprinted in Journal of Political Economy.

Alberto Bisin & Thierry Verdier (2001).

The Economics of Cultural Transmission and the Dynamics of Preferences.

Quarterly Journal of Economics.

***If this essay resonated with you, you can subscribe to my Substack for regular reflections on economics, politics, geopolitics, AI, and literature.

*** Disclaimer: I used ChatGPT-5.2. as an editorial and language-refinement tool. The ideas and arguments are entirely my own, and I take full responsibility for them.

Hey, great read as always. This really builds on your Becker essay. Makes me tink about those 'black box' explanations in other fields too.

Really good deep dive. A lot of things are attributed to preferences when in reality it was probably something different. The work-from-home revolution comes to mind (often erroneously attributed to a change in preferences)